In order to write history, historians need reliable sources. Unless you have information, dependable and supported by documents, letters, diaries, maps or whatever, it is impossible to know what happened in the past. Those sources need to be reliable and credible, because so much that is recorded or remembered is not necessarily accurate. Memories play tricks. People write and record what they consider important, worth remembering, or else they record from a particular point of view. The historian needs to be able to sift the evidence and find out, as nearly as possible, what really happened.

Usually, the most reliable sources are official records, such as census and tax returns, land title records, etc. But what does the poor historian do when these same records contradict each other? How do you choose between opposing accounts? A good example of this dilemma is found in the story of John Strachan French and his family in Burritts Rapids.

John Strachan French came to Burritts Rapids in 1841 along with his wife, Mary Ann, and their three young sons. A daughter was born a year after they arrived in the hamlet. John came from a prominent Loyalist family who had settled near Cornwall after the American Revolution. His grandfather, Jeremiah French, was a Lieutenant in the King’s Royal Regiment of New York where he served for seven years. Jeremiah’s brother, Gershon, was a Lieutenant in Jessup’s Corp, the official who first reconnoitered the Rideau River and surrounding lands and who first identified the South Branch River and the potential mill sites at what would become Burritts Rapids and Merrickville.

The family’s loyalism was even expressed in the names given to the children. John Strachan French himself was named for Bishop John Strachan, a fervent loyalist clergyman who had educated most of the leading men of Upper Canada in his school in Cornwall. One of French’s sons was named after Guy Carleton, later Lord Dorchester, who had organised the evacuation of 30,000 Loyalists from New York in 1783. Dorchester was Governor General of Canada in the 1780’s.

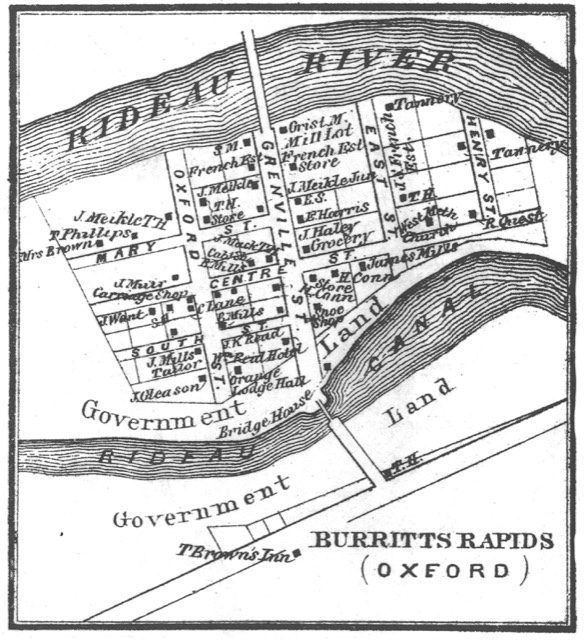

The accepted story of John S. French is that he bought lot 1 on the west side of Grenville Street in Burritts Rapids in 1841, later building a saw mill between his house and the river. The official Walking Tour of Burritts Rapids says that he built the Community Hall as a store and owned a grist mill and shingle mill as well, all located on what is called the Mill Lot across the road from his house. French was a leading member of Burritts Rapids society, and was appointed a Magistrate for Oxford-on-Rideau Township by 1847.

The 1851 Census records that French owned a grist mill worth £1,000 [$4,000], employing four people, a shingle factory worth £350 [$1,400] employing ten people, and a saw mill worth £150 [$600]. A Directory of Businesses in Burritts Rapids in 1851 lists John S. French as owning “grist oatmeal, saw and shingle mills”. Published sources say that he bought the Mill Lot from Terrance Smyth, father of the founder of Smith’s Falls, in 1840. He then sold his milling interests around 1867 to Tom Black. However, as the same publication points out, John S. French died in 1858, so he was not around in 1867 to sell anything.

In fact, French died suddenly, it seems, without leaving a will, and with a lot of debts. His widow Mary Ann was left to calculate the total worth of his assets which she claimed was around £3,000.

All of his property, including lots on East Street in Burritts Rapids which contained a tannery, were seized to pay his debts. Mary Ann remained in their home until she died in 1867 and is buried beside John in the Anglican cemetery in Burritts Rapids.

This would seem to be a fairly straightforward account of the life and times of John French except for a few rather strange wrinkles. The Census of 1851 is quite clear about the assets owned by him and the various publications and information handed down over time provide us with the story as related above. However, other equally official records, specifically the Land Title records which show who owned which property and when, seem to contradict what we think we know about John Strachan French. Which records do we believe and rely on to write his history? Next time, the other side of the story.