SHARE

I remember you

by David Shanahan

It’s all about remembering on Remembrance Day, and phrases are used so easily: “Lest we forget”, or “We shall remember them”. These kind of sayings can become just cliches, if we’re not careful. The familiarity of repeating these same words year after year, of seeing the same wreaths surrounding cenotaphs, hearing the same Last Post being played on a trumpet, or another version of Amazing Grace in bagpipes, all of these can be experienced without ever impacting us, except on a temporary and relatively superficial level.

Every year, the Times has a special issue for Remembrance Day, and this is it for 2021. Rather than remaining general, we try and be specific: to give a brief account of individual men who went through the horrors and trauma of war. A photograph, or some individual fact about one of these men, can provide an opportunity to say “I remember you”, the person, and not just the amorphous mass that are represented in the millions of white crosses in foreign graveyards, or the hundreds of thousands of names inscribed on cenotaphs in every community.

To be completely honest, I find the research involved in writing these short biographies to be deeply depressing. So many young men with lives cut short in tragic and horrific ways. Another of the sayings that become cliches is “they shall never grow old”, and we take a strange form of comfort from that. But the truth is that they never got the chance to grow old, never knew life with a lover, with children and grandchildren. They were fed into a system that threw their lives away before they could properly begin,

Not all of them died in the war. Many came home, but not the same people who left. We know about PTSD now, but more than 3,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers were put on trial by their own side for cowardice, desertion, or refusing to “go over the top” one more time. More than 350 were shot at dawn. Very many were simply ill, and some were clearly not guilty of any of the things for which they were killed. Hundreds of thousands came back with wounds that were more than physical, though those wounds were very real. I don’t think I’ve ever heard of a veteran who was happy and eager to talk about what they had seen and done “over there”. Some things cannot be put into words, even when the nightmares remain.

This issue, we looked at one short period, around the year 1916, because there are simply too many years, too many names, to cover in one issue. And these individual men deserve a memory. It was a very bad year, as they all were. But 1916 saw the Battle of the Somme. We think of battles lasting hours, even days; but the Somme went on from July until November. Casualties were unbelievably horrendous, but no-one is really sure of exact numbers. Officially, over a million men died on both sides, including 24,000 Canadians. That was just one battle in the four years of catastrophe.

It is right, even essential, that we remember this, and those men who died, were wounded, came home broken. But that is not easy. Our annual memorials are clean: clean uniforms and clean cenotaphs. No veteran who lived through the 1914-1918 war remains to tell us the realities of that time, so we have to make an effort to find out. Soon, the same will be true of 1939-1945. Then all we’ll have left are the little bios, the photographs, the written records.

I’ll be very honest here: I find the whole thing deeply upsetting. I don’t like putting this issue together every year, because I’m never sure if we do the young men justice, not properly. And I’m angry, really deeply angry, that they were put through all of that because three cousins, the Kaiser, the Czar and the King of Britain, put ego and boasting before the lives of their people. Because it wasn’t the War to end War, it just part 1, and part 2 came just thirty years later. More slaughter.

One thing that came out of WWI that was different from other wars: the actual men were remembered in monuments and cenotaphs, not just the generals and the kings. This wasn’t out of a change in their status in society. It was because of the enormous impact that losing a generation of young men had on communities. Young women, parents, and younger siblings kept their memory alive. In the Commonwealth and Britain, this led to Remembrance Day. In other countries, it led to revolution and the downfall of those empires that had sparked the war. By 1919, only the British Empire survived, and it was mortally wounded. The new empires were rising: the United States and Russia. Part two would see them consolidate their positions.

I don’t know. Is this all too little, too late? Can we, should we, continue to remember this way? I have an idea: instead of repeating the moral blackmail of Flanders Fields, with its warning that the dead would not rest if we didn’t remember them, let’s try and pick one man each year to remember. Sadly, there are names on cenotaphs everywhere, including our own community, that have names inscribed for whom there is no information. We know nothing about those men, for some reason.

So, this Remembrance Day, however you mark it, maybe you could pick one of those names and spend the day thinking about them, wondering who they were and who they may have left behind, if anyone. Think of them and say, “I remember you”.

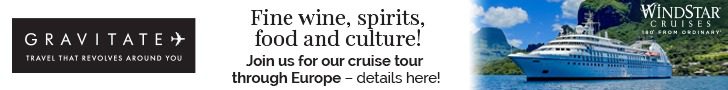

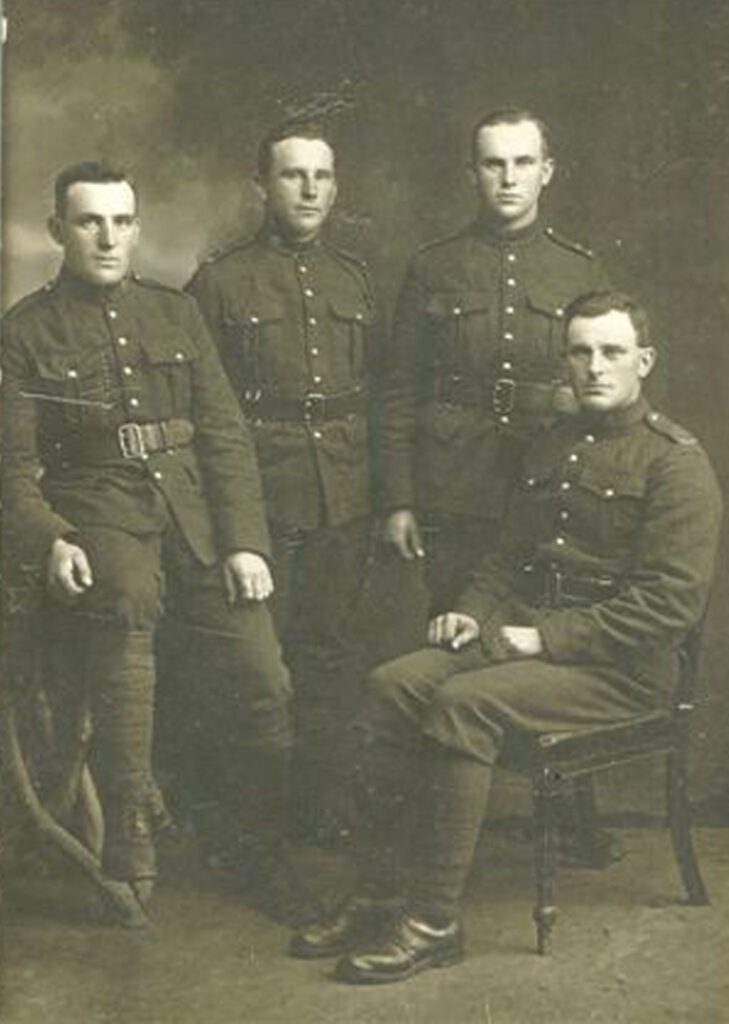

WWI image

This panoramic photograph of the Canadian Expeditionary Force was taken at the new military camp at Val Cartier, Quebec in late 1914. It was taken by the Panoramic Camera Company of Toronto and printed by the Montreal Star. Canada was not prepared for war when it came in 1914, and it became necessary to call up the various Militia Regiments for service abroad. An Order-in-Council was passed by the Governor General in Council on August 6, 1914 under Section 69 of the Militia Act authorising the Militia to be put on Active Service. That same day, General Order Number 142 listed the regiments to be called upon. The Third Division of the Canadian Expeditionary Force included the 56th Grenville Regiment (Lisgar Rifles).

Kemptville was at the centre of the call-up, the Armoury in Riverside Park, which had replaced the old drill halls at Millar’s Corners and Burritt’s Rapids, had only been opened the previous month, and a Cadet Corps had been set up at the High School in May. Now, it was all for real and the people of Oxford-on-Rideau, South Gower and the Village of Kemptville were going to war.

Canadian volunteers

Between the beginning of the war in 1914, and June 30, 1917 when conscription was being debated in the House of Commons, 42,456 Canadians had volunteered to enlist. Of that number, around 320,000 had actually gone overseas. The total of these that had been killed, were missing, died of other causes, and captured was 32,000. In July, 1917, casualties had totalled 3,637 and the number of new recruits enlisted that month was just 4,257.

War Amputee Veterans started 100-Year Legacy

by Martine Lepine

Of the thousands of Canadian soldiers who were wounded while serving in the First and Second World Wars, many returned home missing limbs. United by a common bond of amputation, these veterans not only served their country during wartime, but they made a difference in the lives of generations of amputees that continues today.

In 1916, on the battlefields at Ypres in Northern Belgium, Sidney Lambert (1887 – 1971), a Lieutenant Colonel and Army Padre, lost his left leg above the knee.

While recovering at a hospital in Toronto, Lambert conceived of the idea of a national association to bring together, support and fight the battles for amputee veterans, today known as The War Amps. In 1920, he became the first Dominion President of the Association and worked tirelessly to bring veterans issues before the government.

It was these First World War amputee veterans, like Lambert, who welcomed the new contingent of amputee veterans following the Second World War, helping them adapt to their new reality and sharing all that they had learned.

One of these was Neil Conner (1918 – 2012) who served as a navigator with the Royal Canadian Air Force. He was injured when his plane was shot down near Bremen, Germany, resulting in the loss of his right leg below the knee.

Another was Bert Coulson (1921 – 1979) who served with the Canadian Army and lost both of his legs below the knee due to injuries sustained while serving in Emmerich, Germany.

Along with their fellow War Amps members, these veterans went on to provide support to civilian amputees. Coulson said the best way to help was to “roll up my pant leg and show them we can dance, bowl, hold down a normal job. It’s what you have left that counts.”

The War Amps veteran members established the Key Tag Service, which is still going strong today, to fund the Association’s many vital programs for amputees across Canada.

Rob Larman, a Director at The War Amps and a leg amputee himself, said Mr. Lambert, Conner and Coulson proved that they would not let their amputation hold them back in all aspects of life.

“Though they considered themselves to be ‘ordinary guys,’ our founding veteran members have left a legacy for generations of amputees that has gone on for 100 years and counting,” said Larman. “On Remembrance Day especially, but also throughout the year, we pay tribute to their sacrifice and service.”

Celebrating stories of Ontarians:

André Levesque, Member of the Order of Ontario

Whenever André Levesque walks by the National War Memorial in his native Ottawa, he lays his hands on the tomb of the Unknown Soldier. “My body feels warm and glowing,” he says, “like I’m going through something very emotional. It’s amazing.”

André’s deep personal connection to the monument was sparked when he worked as the project manager for the repatriation of the soldier’s remains. He led the team that chose the unidentified Canadian from a cemetery near Vimy Ridge, had the remains flown over from France, and reinterred them, at a ceremony in 2000 attended by some 20,000 people. Shortly thereafter, he project-managed the establishment of the National Military Cemetery at Beechwood in Ottawa, where he is now chief historian. His citation for the Order of Ontario, to which he was appointed in 2020, notes that he is a “pioneer of memorialogy, the study of memorials and commemoration.”

André became fascinated by veterans’ stories, and the need to preserve them, when he joined the Canadian Army Reserve as a high school student in 1974. He met veterans of the Korean war and the Second World War: “These soldiers were doing hard work—liberating, going through Italy, France, The Netherlands, being shot at, being wounded. When they pass away, you’re trying to achieve your own closure, from having met them to remembering them.”

In 2001, he set up the National Inventory of Canadian Military Memorials; currently, it lists over 8,200—more of which are in Ontario than any other province. He also runs the website memorialogy.com, in his capacity as chair of the International Society for Commemoration, Memorials and other Monuments. Together with contributors from North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand, he delves into, and writes about, the history specific monuments represent—related not only to war, but also to such diverse areas as sports, medicine, the environment, and race relations. “I’m super-interested in putting together the fabric of the history of Canada, involving all kinds of aspects,” he says.

Today, André is putting his research into practice: he co-leads the team that has commissioned, designed, and overseen the construction of the new Amicitia France-Canada monument in Beechwood Cemetery. It recognizes the shared history, heritage, and diplomatic relations between the two countries, and will be officially unveiled in the coming months.

“We wanted the community to feel there’s part of themselves in there,” he says. Community involvement, he explains, is crucial to monuments’ relevance and longevity. For many of them across Ontario, maintenance can be a challenge, particularly when the local associations that commissioned their construction have themselves faded away. “We’re hopeful that local schools and municipalities will encourage their citizenry and the youth to be involved with activities that include remembrance and commemoration,” he says. “That doesn’t mean that you have to commemorate war—we’re talking about remembering the people.”

The Honourable Elizabeth Dowdeswell, Lieutenant Governor of Ontario, issued this statement: “On November 11, as Ontarians gather throughout our province, let us build on the community spirit that has inspired the creation of so many memorials. Let us reflect on how learning and sharing the stories of those who serve, and each other’s stories too, will help foster the empathy and understanding upon which we can build a more just and resilient society—one that is worthy of our soldiers’ sacrifice.”

One of a Lieutenant Governor’s great privileges is to celebrate Ontarians from all backgrounds and corners of the province. Ontario’s honours and awards formally and publicly acknowledge the excellence, achievements, and contributions of role models from all walks of life. In doing so, they strengthen the fabric of communities and shape the aspirations of Ontarians. Learn more: https://www.ontario.ca/page/honours-and-awards

North Grenville’s Fallen

(Age in brackets)

1914 – 1918

Major Horace Hutchins 1917

Captain John McDiarmid (40) 1916

Lt. Charles Elwood Oakes (26) 1916

Sgt James Arnold Dillane (20) 1918

Sgt Robert Jay Bennett (26) 1918

Sgt. Robert Percy Barr, DCM (19) 1917

Pte G. Grey No information

Pte Edmund Roy Mackey (24) 1918

Pte Harry Johnson Carson (23) 1917

Pte Harold Melvyn Maxwell (19) 1918

Pte Nelson Bazil Laplante 1918

Pte Cyril Douglas O’Leary (23) 1918

Pte Ambrose Arcand (23) 1918

Pte Thomas Augustus Arcand (29) 1918

Pte H. Andrews (22) 1917

Pte John Edgar Arcand (24) 1918

Pte William Algy Stewart

Pte Charles Acey Hurlbert (20) 1917

Pte Martin Leo Carlin (20) 1917

Pte John Moran (19) 1918

Pte Thomas James Beckett (22) 1918

Pte Alfred Caley (31) 1918

Pte Ernest Rupert Davie (18) 1917

Pte George Gordon Howey (33) 1918

Pte John Edward McCrum (24) 1917

Pte Harvey Milburn McCrum (31) 1917

Pte E. Hastings No information

Pte A. Irvine No information

Pte S. Hudson No information

Pte Walter Copping (23) 1916

Pte John Arthur Jeffrey (18) 1918

Pte Jesse Humphrey (25) 1917

Pte Archibald McDiarmid (33) 1916

Pte Albert Edward Worles (20) 1915

Pte A. Scott No information

Pte Isaac Cooper (35) 1916

Pte John Allan Stewart 21) 1918

1939 – 1945

Lance Bombardier Henry W. Cowie (21) 1944

Gunner Arthur Stewart Robinson (24) 1944

Pte Donald Lee Crawford 1944

Leading Aircraftman Byard B. Black (47) 1943

Trooper George Joseph Wagner (23) 1944

Pte J. Shearer No information

Pilot Officer William Lysle Buchanan 1942

Flight Sgt Harry Lyle Brown (20) 1943

Flight Sgt Guy James M. McElroy (21) 1942

Flight Sgt D. D. Taylor (19) 1941

Sgt Patrick Redmond Roach (19) 1941

Corp. William Harold Edgar Leach (24) 1941

Pte Blake Williamson (23) Afghanistan 2006

The Home Front

One of the major consequences of the war on the home front in North Grenville was a scarcity of fuel. On October 18, 1917, the following appeared in the Weekly Advance:

Fuel Scarce

The fuel situation in Kemptville and vicinity still remains acute, neither dealer having received any coal for a month. Anderson & Langstaff received a couple of cars this week, mostly for their own use, what they did sell brought eleven dollars a ton. At Oxford Mills no coal at all has arrived this season. Would it is scarce owing to the deep snow in the woods last winter but little was cut, and those who have it for sale won’t part with it yet for fear they may sell it for less than they could get should they hold it. Should the coming winter be a severe one the outlook for hardship and suffering is to be expected.

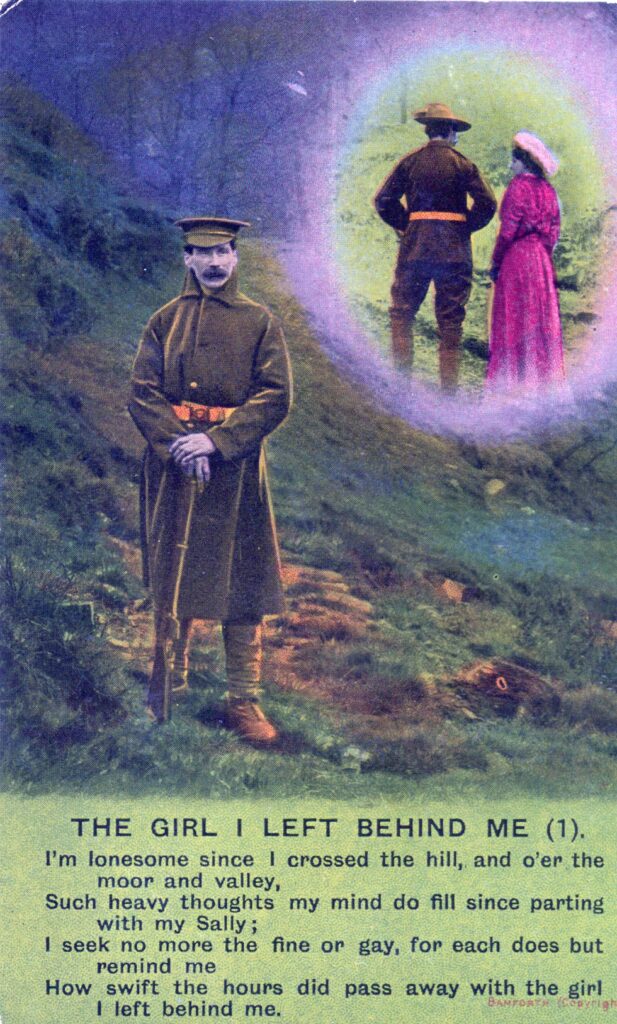

Harry Carson

Harry Johnston Carson was born in Mountain, but he and his father operated Carson’s Blacksmith shop on the south-east corner of Asa and Thomas Streets in Kemptville. Harry enlisted in March, 1916. In June, 1917, he joined his unit at the front in France, and he was killed in action on August 23, eighteen days after being deployed in the trenches for the first time. He was aged just 25.

In his will, Harry left everything he owned to his wife, Jesse May, who was left to look after their three daughters, the youngest of whom was only eight months old. Harry never saw his youngest child, who was born two months after he left for France.

Private Ernest Rupert Davie

Ernest Davie was the son of William and Charlotte Davie, of Oxford Mills, a mail carrier by profession, who enlisted in the 20th Battalion, Canadian Infantry, on December 9, 1915. He was one of the very many young men who went from rural Ontario to die in France, aged just 18, on April 5, 1917. Ernest was of six such men from Oxford Mills to die in World War I. He had attended St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church in Oxford Mills, and is buried in the Ecoivres Military Cemetery, Pas de Calais, France.

The McCrum Family of Oxford Mills

The McCrum family traced their Canadian roots back to 1831, when Edward and Elizabeth arrived from Ireland and settled on lot 11, concession 8 in Oxford-on-Rideau Township, between Patterson’s Corners and Bishop’s Mills. Elizabeth lived to watch her grandsons, John and Milburn, grow up on the farm. John enlisted on January 3, 1916, when he was 23 years old and living in Saskatchewan. His mother, Fannie, was a widow living in Oxford Mills. John was wounded on August 18, 1917 and died at #58 Casualty Clearing Station in France, of wounds received on August 18, 1917. He had only been at the front lines since June. He was 23 years old.

Harvey Milburn McCrum was John’s older brother. He had enlisted a few months before John, on October 25, 1915. Like his brother, Milburn, as he was called at home, was living in the west at the time, in Alberta. He was wounded in action in September, 1916, three months after arriving at the front, but later returned to his unit in the 49th Battalion. He was killed in action near Rouen in Belgium on October 13, 1917, just two months after John. He has no known grave. He was 31 years old at the time of his death. Milburn left a widow behind, Agnes, along with his young child, who had moved back from Edmonton to Oxford Mills after Milburn enlisted.

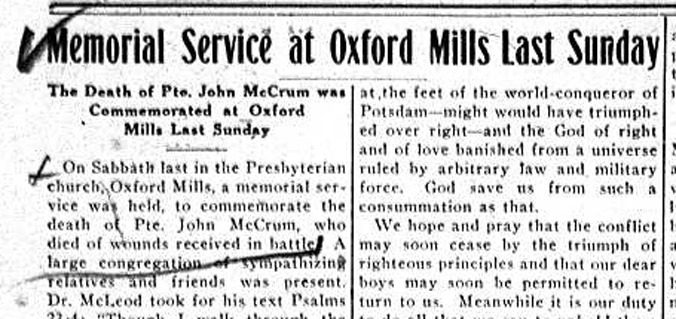

When news of John’s death reached Oxford Mills, a special service was held in the Presbyterian church there, during which the following, sadly ironic, comments were made:

“Since last we met here as a congregation of worshippers one of our members, Mrs. McCrum, received the sad intelligence that her son John had succumbed to wounds, received in battle, in a hospital in France. We wish to express to her and to all the relatives and friends our sincere sympathy with them in their sad bereavement. Today’s services intended to be a memorial one to commemorate the death of one who made the supreme sacrifice for the maintenance of liberties and rights which we regard as better than life itself. We have not the body with us: it lies with many other Canadian heroes yonder in Flanders. But his memory remains the most precious and sacred one to those who love to most – mother and sisters, and brother, the latter of whom is also in the service of his King and Country in the front trenches on the battlefield. To be the mother of two such heroic sons is no small distinction. But it is a distinction that has to be purchased at the price of a great sacrifice. Few of us, if any, can enter into the keenness of the sorrow that pained that mother’s heart when the word came that her dear boy had been taken from her. The sisters, too, deserve as they receive our utmost sympathy in the terrible grief that has so suddenly entered their young lives. As for the brother, we join in the prayer to Almighty God that he may be preserved through this awful struggle and be brought back safely to his loving mother, sisters and devoted wife and child.”

Oxford Mills

The tragedy of the great war is being brought home to the people of this community, more and more closely as the days go by. Last week we were called upon to mourn the loss of one of our brave boys in the person of Pte. John McCrum, who died of wounds “Somewhere in France”… This week brings to us another sad message from the front, and is brought with it much sorrow, and has awaken feelings of sincere sympathy for the family and intimate friends of the brave soldier, our esteemed townsman, Teddy Greer, of whom the cablegram tells, he has been seriously wounded. We all join in the earnest hope that he may speedily recover from his injuries and may return safe home.

[Weekly Advance, September 6, 1917 Edward “Teddy” Greer did survive to return home after the war].

Oxford Mills

The tragedy of the great war is being brought home to the people of this community, more and more closely as the days go by. Last week we were called upon to mourn the loss of one of our brave boys in the person of Pte. John McCrum, who died of wounds “Somewhere in France”… This week brings to us another sad message from the front, and is brought with it much sorrow, and has awaken feelings of sincere sympathy for the family and intimate friends of the brave soldier, our esteemed townsman, Teddy Greer, of whom the cablegram tells, he has been seriously wounded. We all join in the earnest hope that he may speedily recover from his injuries and may return safe home. [Weekly Advance, September 6, 1917 Edward “Teddy” Greer did survive to return home after the war].

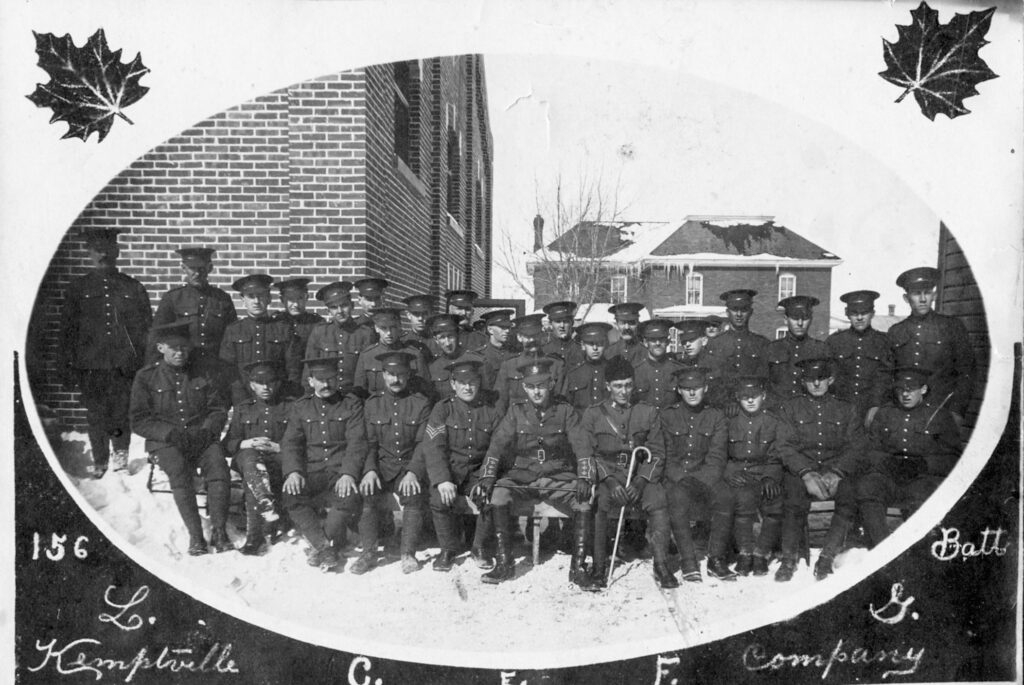

Feb 1916 Kemptville

The Kemptville Company of the 156th Leeds & Grenville Battalion photographed outside the Armoury in Kemptville in February, 1916. Seated centre front is Captain T. Ashmore Kidd, who had just returned from Europe where he had been paymaster to the battalion. T. A. Kidd joined the Grenville militia and was commandant of the 56th Lisgar Rifles in Kemptville in June, 1914 when the new Armoury building opened in Riverside Park. He had started the Cadet corps at the High School in Kemptville in May, 1914. With the outbreak of war in August, Thomas went abroad with the First Canadian Contingent and was badly wounded at the battle of Ypres the following year. He held staff jobs thereafter, and was Quarter Master General to Medical Detachment No. 3 at the end of the war. He took charge of reorganising the Grenville Regiment between 1920-25.

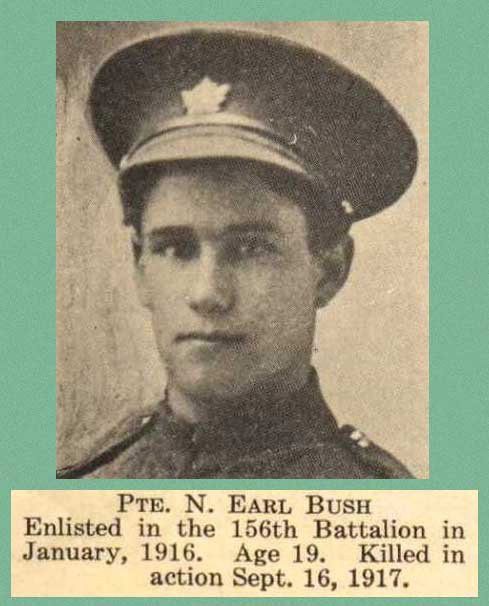

Private Norman Earle Bush, 639411

Norman Bush was born in South Mountain on March 4, 1897, son of Theodore Bush. Norman was a labourer who joined up in Merrickville on January 21, 1916 when he was 18 years old. There was no height requirement at the time, as Norman stood just 5 ft. 2½ inches tall. The link with Merrickville was through his grandmother, Melissa Briggs, who had been his foster mother growing up. Norman named her as his beneficiary in his will, drawn up before he was sent to France on May 1, 1917.

There were usually some small details recorded in the files that give some personal insight into these young men. Norman is described as having feet that were “slightly flat”, and with ringworm scars on his face between his ear and eye.

Norman arrived in France on May 24, 1917 and was transferred to the 2nd Battalion of the Canadian Infantry Regiment, arriving in the trenches on June 27. Just less than three months later, Norman was killed in action near Rouen. His battalion was due to be relieved that night, but somehow, Norman died before he could leave the front. He is buried at Aix-Noulette Communal Cemetery Extension, Pas de Calais.

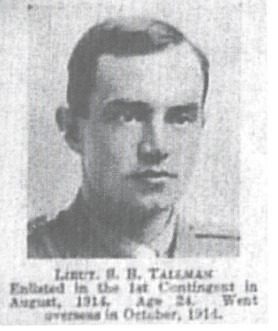

Lieutenant Stanley Tallman

Stanley Bliss Tallman was born and raised in Merrickville, and when war broke out in 1914, he was working as a Bank Clerk. He signed up almost as soon as recruitment began, on September 24, 1914, having already a year’s experience with the 56th Lisgar Rifles. He was 22 years old at the time he joined up, and trained at Valcartier in the Royal Canadian Dragoons. The family was a prominent one in Merrickville, Stanley’s father had been Reeve of the Village in the past.

Stanley went through the entire four years of war, being promoted to Corporal in 1916. In December, 1917, he attended the Cadet School at the Shorncliffe Military Camp in England, before being promoted to Lieutenant in April, 1918. Much of that last summer of the war was spent on various training courses, before rejoining his regiment on July 29, 1918.

But Stanley’s life was cut short, just six days before the war ended. The records do not make it clear whether he suffered from the same plague that was to take so many millions more around the world in the coming year, but he fell ill with Pleurisy on October 15, and was taken to a hospital in Rouen, where he was declared seriously ill. That diagnosis was changed to Dangerously ill two days later, and he was transferred to the London General Hospital in England on November 2. He died of pneumonia on November 5, 1918, aged 26. Stanley Tallman is buried in the Brockwood Military Cemetery near London.

The story of the Watt family and their role in both World Wars is quite amazing. James and Eliza Watt had four sons, all of whom enlisted in the First World War. William Lloyd Watt enlisted in the Canadian Infantry, 44th Battalion, and was killed in France on June 3, 1917. His brother, Richard Norman, died in France just over two months later, on August 27, 1917. William was 24 years old and Richard was 27. Their two other brothers survived the war.

One of these, Clarence, re-enlisted during the Second World War, along with his three sons. Two of them, Norman Alexander and Alastair Clarence Watt, were killed while serving in the Royal Canadian Air Force. Flying Officer Norman Watt died on July 1, 1943, when his Spitfire was shot down over England. He was 21 years old.

Flying Officer Alastair Watt was killed on March 17, 1945, when his Lancaster was shot down over Germany, just weeks before the end of the war. He, too, was 21 when he died. His father and brother survived the war, although their brother, Corporal Leslie Watt, was badly wounded in France and returned to Canada with a permanent injury to his arm.

The sacrifices made by the Watt family of Merrickville are a stunning reminder of the sacrifices made by the people of Merrickville-Wolford in Canada’s wars of the Twentieth Century.