International Women’s Day used to be a controversial concept for men: why should there be a day just for women? Is that not sexist? It was all based on a misunderstanding of what and why the day was meant to be, I think. Women may agree that men are, generally speaking, a bit self-absorbed and slow to see what’s in front of their face. As a man, I disagree completely: slow is too positive a word! The fact is that I remember, when I was growing up in the 60’s, that the rise of feminism and the initial push for women’s rights at that time was confusing. The order that society accepted had been in place for a long time, or so it seemed. It took time for both women and men to be educated, informed of their own history. What was a “natural” woman?

The role of women in both World Wars, and their subsequent return to “domestic bliss”, was something that was not well-known to my generation. The history that went further back even than that was a closed door for most people. And it wasn’t always men who found it hard to grasp what was happening in society as the logic and basic justice of the arguments for women’s rights were increasingly put in front of us. I remember that when my eldest daughter was a few months old, I was the parent who brought her to the creche every morning on my way to lectures in university. At lunch, when parents had to be on hand to give staff a break, I was the only man there. And the staff started to refer to “David and the other mothers”.

Thankfully, these days men are far more likely to be involved in parenting, with all of its challenges, and there has been a shift in attitudes generally towards the relative roles of men and women. But, I guarantee that someone will be offended by a man writing an editorial for International Women’s Day, and some will find something sexist in how I say things. So be it: we’re all on the way, and we haven’t arrived yet. But major steps have been taken on that journey.

Every week, the Times is produced by a staff where women outnumber men by 2 to 1. Women have taken a leading role in every sphere of life, private and public. Much has been changed, and much remains to be achieved. On International Women’s Week, 2024, we can look back a century and see how much of the progress had to be fought for on every level, especially under the law.

The Suffragettes of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century were often veterans of earlier campaign for rights, such as abolition of slavery, amelioration of child labour laws, or the amazingly powerful campaign for Temperance and Prohibition that lasted into the 1930’s. Organisations like the Women Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) gave women experience of running national movements, political campaigns, and sharing executive positions with men. The LCBO was established as a compromise on the Temperance-Prohibition issue by the government of G. Howard Ferguson, native of Kemptville and one-time Reeve of that Village. Ferguson’s mother had been very active in the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which may have had an influence on his policies as Premier.

The WCTU was a very influential organisation for many reasons. Not only was it part of a worldwide network campaigning for prohibition of alcohol, it also provided women with experience of political activism at a time when there were few outlets for such interest. Like the Sons of Temperance, the WCTU gave women an equal voice in political, educational and social activism in the nineteenth century. Built, as the name suggests, on an evangelical Christian base, the WCTU learned from experience that, without the vote, women were severely limited in what they could achieve. The Union broadened its scope and worked for enfranchisement of women, better education for all classes in society, and improved working conditions for women and working class men. An illustration of how these women thought is seen in an 1899 statement: “Woman: first in war, first in peace, first in the hearts of her country, last at the ballot box”. In fact, the first time women were given even a limited vote in Ontario was in the plebiscites on prohibition. Two of the Famous Five women who won constitutional recognition of women as “persons” in the 1920’s, Nellie McClung and Louise Crummy McKinnon, belonged to the WCTU. Historians refer to such activists as “evangelical feminists”, another phrase that requires a rethink of assumptions in today’s society.

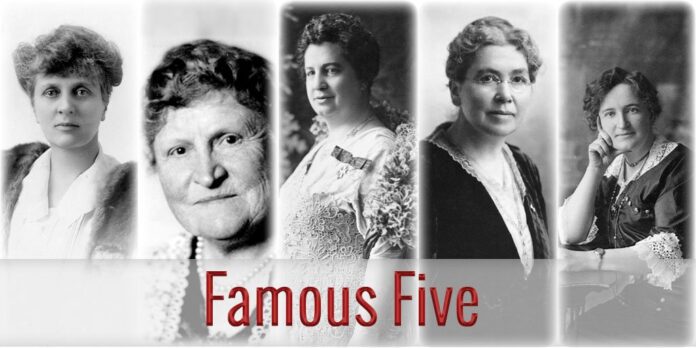

Although Agnes McPhail was the first woman elected to the House of Commons in 1921, women were still denied the right to become a Senator, as the British North America Act of 1867 required that they be “persons”, which successive Canadian Governments had decided was a term that did not apply to women. In August 1927, Emily Murphy invited four prominent women activists Nellie McClung, Irene Parlby, Louise McKinney and Henrietta Muir Edwards, to join her in sending a petition to the Canadian government regarding the interpretation of the word “persons”. These women are known today as The Famous Five.

On 27 August 1927, the Famous Five signed the letter, which was sent to the Governor General.

In 1928, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that women were not “persons” according to the British North America Act. Therefore, they were ineligible for appointment to the Senate. However, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council reversed the Court’s decision on 18 October, 1929. The Persons Case enabled women to work for change in both the House of Commons and the Senate. It also meant that women could no longer be denied rights based on a narrow interpretation of the law. They were now, legally and forever, “persons”.

Much done, much still to do; but the attitude of society overall has been radically changed over decades. A slow process, and one that requires International Women’s Day to keep it at the forefront of hearts and minds.