The politicians and the people of the United Province of Canada looked with something close to despair at the apparently hopeless state of affairs to which their province had been reduced. On June 14, 1864, the administration of John A. Macdonald and Etienne Taché had been defeated in the Assembly after just two weeks in office, the latest in a very long line of governments that had failed to establish a stable and workable administration. There was a feeling that nothing could prevent another political fiasco.

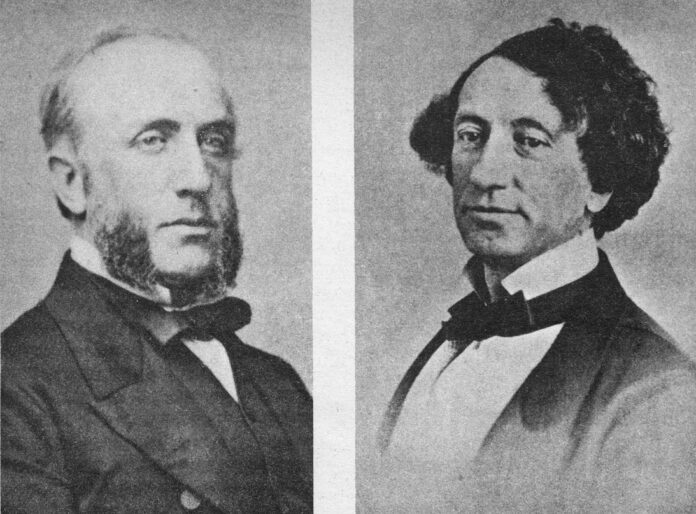

Then George Brown, editor of the Globe newspaper, seen in Francophone Canada as a bigot, racist, hardliner and an opponent to any French influence in Canada, made a startling gesture that took everyone by surprise. He proposed a working agreement between his group, the Liberals, or Grits, and that of Macdonald, the Liberal-Conservatives, based on a determination to make either a federal Canada, or a Union of all of the British North American colonies.

On the day the Macdonald government had fallen, Brown had introduced to the Assembly the report of a committee he had put together that May to look into both of these ideas. Strong in his views as he was, Brown recognised that something new had to be attempted, so when the committee members, including Macdonald and George Etienne Cartier, met for the first time, he locked the door and put the key in his pocket. “Now gentlemen,” he said, “you must talk about this matter, as you cannot leave this room without coming to me.”

Surprisingly, they did talk and they came up with the outlines of a scheme. Even more surprising, when it was put to a vote in the Assembly, it passed with a majority of the members voting in favour. Macdonald, Cartier, and even some of Brown’s allies, voted against it. However, now Brown’s offer of a coalition seemed the only possible way forward, the news of the deal they reached was met with rapturous applause and relief by most people. But not all.

Brown’s reputation, especially in French Lower Canada, and among Catholics in the Upper part of the Province, was so bad that this Great Coalition was met with deep suspicion and many reservations. Even Brown’s own party wondered if perhaps he had become a turncoat and was now in the pocket of the wily Macdonald.

The fact is that George Brown had broken the deadlock: his generous and visionary move had led to a completely new political scenario, one where a greater idea of the future of British America became possible. It has been suggested that his new and more conciliatory approach to politics may have been caused in large part by the fact that, unlike before 1863, he was now a very happily married man and father, mellowed perhaps, by the experience. Does Romance lie at the heart of the Canadian Confederation?

Even having taken this giant step forward, Brown was deeply reluctant to actually take office in the new coalition government, preferring to return home to family and the Globe. But encouraged by his colleagues and friends, among them Thomas D’Arcy McGee, a young Irish journalist who was about to play his own great role in the story of Confederation, Brown agreed to take up office and see the project through. But which project would it be?

Brown personally preferred having Upper and Lower Canada become a federal union, rather than the legislative one it had been since 1841. But the majority favoured trying to create a federation of all the British colonies in North America: Confederation, as it came to be called. This would mean entering into talks with the Lower Colonies, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, as well as, possibly, Newfoundland. And it just so happened that the newspapers were filled with reports that those very colonies were planning a conference to discuss their own federation proposals, Maritime Union. This would be a federation of the three, or four, provinces, a new Acadia. This would be a return to the situation that had once existed when both New Brunswick and PEI had been part of Nova Scotia.

The idea for a Maritime Union had been around as long as the Confederation scheme, but little had been done to move it forward until the young Lieutenant Governor of New Brunswick, Arthur Hamilton Gordon took to the idea and pressed it strongly on both his superiors in London and the politicians in the Maritimes. The three Assemblies agreed to hold a conference on the matter at some point. It was at that moment that the new coalition government in Canada dropped a hint that they would like to be invited along. Things were going to start moving very quickly indeed.