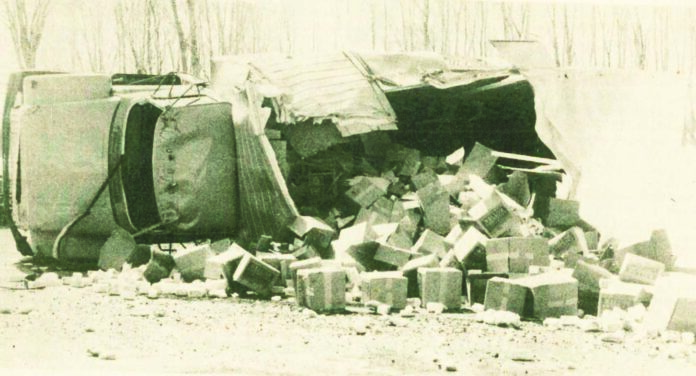

By early summer of 1976, the immediate consequences of the Buttergate controversy seemed to have died away. A joint investigation by the OPP’s Criminal Investigation Department and the Kemptville Police into the theft of almost 7,500 pounds of butter from an overturned creamery truck on April 9, 1975, had identified 27 individuals in the town who had come into possession of various quantities of the stolen goods, some as much as 1,000 pounds of the stuff. This included Mayor Ken Seymour, who had claimed that the 200 pounds of butter found to have made its way to his property had been left on his front porch and in his car by persons unknown. Nevertheless, rather than hand it over to the police, the Mayor had apparently “distributed” it around the town.

Given that so many individuals had been identified as having received stolen goods, it was a surprise when only three of them were actually charged, and even more surprising that the courts decided there was not enough evidence to convict them. But that was the situation in June, 1976 when the legal proceedings ended and it looked like the entire incident would be relegated to Kemptville’s colourful history.

But this was one of those unusual times when events in small-town Kemptville had impinged on the consciousness of the nation, and people in positions of political power had taken an interest in the Buttergate controversy. Following the staying of charges in the case, the Ottawa Citizen ran an article on May 25, 1976 in which it was suggested that political pressure had been brought to bear on the police investigators to minimise the extent of the prosecutions, particularly in the case of Mayor Seymour. Ontario Attorney-General, Roy McMurtry decided to set up a committee to look into the allegations.

Kemptville Police Chief Steve Kinnaird stated clearly that he had found himself in an awkward position having to investigate prominent citizens of Kemptville, which was why the OPP had been brought in to help. The Deputy Commissioner of the OPP, L. R. Gartner, testified that it had been the decision of the Crown Prosecutor, John Vamplew, that there was not sufficient evidence to charge Mayor Seymour. Mr. Vamplew agreed with that testimony, but threw the responsibility back on the OPP by stating that they had not recommended laying charges against the Mayor in the first place.

The Deputy Commissioner flatly contradicted that, and repeated that it was the Crown Prosecutor’s decision not to lay charges. It was then revealed that the original plan had been to charge four people, including Mayor Seymour, though only the other three were ever prosecuted.

Solicitor General John MacBeth then got involved, objecting to having the issue debated in public in the first place. He reprimanded Deputy Commissioner Gartner for revealing the discussions around charging the mayor, stating that “generally we don’t do trials in the press”. The next day, Gartner changed his testimony, claiming that he had been misunderstood: the OPP had never recommended charges against the mayor. Membrs of the Committee wondered aloud about whether this change of testimony was another result of political interference in the saga of Buttergate.

The Committee’s work ended without reaching any conclusions when the Assembly closed for the summer break. For a few weeks, the Buttergate story had occupied the Ontario Legislature and the press, with extensive coverage in both Ottawa newspapers. Given the level of interest and the colourful details of the story, it was only natural that the local newspaper would have been full of the twists and turns of the saga. In fact, the Kemptville Advance published…not a single word! No mention was made of the exciting proceedings of the Committee in Queen’s Park, nor of the ongoing controversy surrounding Mayor Seymour. In fact, the regular report from Queen’s Park by local MPP Don Irvine continued to appear regularly, without a mention of the Committee, Buttergate, or the continuing fascination Kemptville was having on the provincial legislature. More political influence?

Relations between the Kemptville Police and local politicians were strained, to say the least. In September, 1976, the Town Council’s Police Committee launched a scathing attack on the professionalism and commitment of Chief Kinnaird and his officers, accusing them of “not co-operating”with Council and not being “congenial”. Council then laid off the Police Department’s part-time Secretary. Chief Kinnaird was forced to issue his own rebuttal the following week, pointing out the amount of work being performed by an understaffed force, and refuting each of the accusations that had been made against his Department.

At the end of the year, Ken Seymour announced that he would not be running for re-election as Mayor of Kemptville. Perhaps some peace was restored in those elections, when the Chair of the Council’s Police Committee was acclaimed as Reeve, and Chief Kinnaird’s brother was elected Deputy Reeve. Buttergate was then consigned to history.

I remember hearing about this sometime after moving to K-city in the 1980’s.

What a story! I never knew ANY details.

Thanks for sharing this on line as I sometimes miss reading the print edition.

– Reg