by Fred Schueler, Fragile Inheritance Natural History

On 27 September, Kate Queen wrote to the NG Times: “I would love to hear Fred Schueler’s thoughts on the European Wild Buckthorn. I am fighting what feels like a losing battle against this tree (shrub?) I wonder how best to control the spread.”

In Limerick Forest and much of eastern Ontario, invasive shrub and Buckthorn are synonymous, and, in different areas, dense stands of one or both species really reduce the habitat and growth of forest floor herbs and tree regeneration. They both bear crops of shining black berries. The Buckthorns are alternate hosts of Puccinia rusts of cereals and other grasses, and toxins in the leaves restrict the species of other plants that can grow under the Buckthorns. They may also poison tadpoles in nearby ponds. Both species sprout enthusiastically after they have been cut back. It seems that you can add Buckthorn to just about any adjective to form an English name for a species in this group and as soon as such a combination achieves currency, it will be abandoned. I’ve chosen to use frightening-sounding adjectives based on the scientific names here, but there’s no real consensus for either species.

Cathartic Buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica). Other names: European, Purging, or Common Buckthorn. Characterization: The dark-barked semi-shade tolerant small-leaved Buckthorn, with lenticel-barred twigs often sharpened into thorns. The leaves are dark green, and are shed late in the fall, forming billows of green under the borer-killed Ashes in Ottawa, and increasingly in the country. Usually a shrub, it can grow into a tree 10 m tall, and one with a 25 cm diameter trunk at an old homesite near Domville might have been taller than this if its crown hadn’t been broken.

Native species displaced: All fencerow, edge, and open-field shrubs, especially Hawthorn, Dogwood, and Canada Plum.

Uses: Used medicinally as a laxative. Fairly palatable to goats and rabbits, berries eaten by late-winter birds. Bald-faced hornets chew away patches of the bark in the spring. The hard wood of the larger plants is used by turners and is a superior firewood. Urine of mammals that browse the twigs is bright blue after exposure to sunlight.

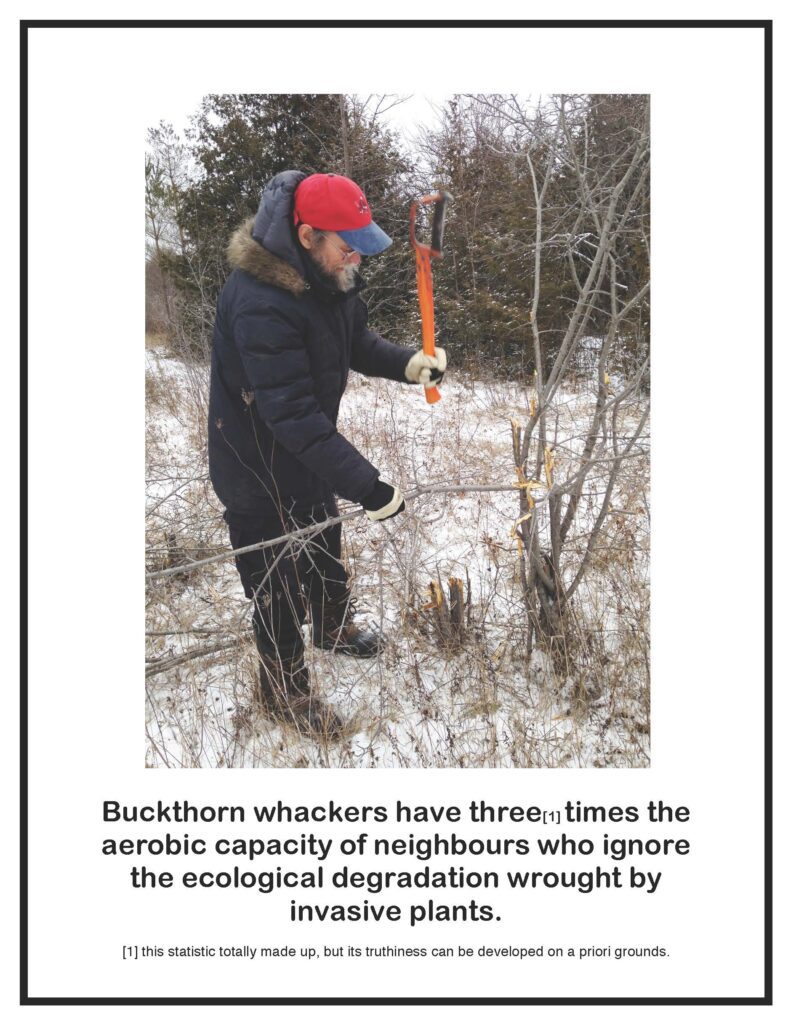

Prevention: Recreational slashing. There are uprooting devices for pulling out the roots of cut shrubs. Licensed applicators can use herbicides to kill stumps, and a native fungus has recently been domesticated and sold as a powder to do this. The seeds are widely distributed by the droppings of birds, as well as by falling beneath the parent plants, and vast numbers of these can be pulled by hand.

Frangulous Buckthorn. (Frangula alnus) Other names: Called Rhamnus frangula in older documents; Glossy, Smooth, Alder, Columnar, Tallhedge, European, Black, or Shining Buckthorn are used as English names.

Characterization: The shade-tolerant wide-leaved Buckthorn, with thornless speckled twigs, and light fragile wood (“frangulus” means easily broken), the leaves turning yellow-orange in the fall. Omnipresent under pine plantations in parts of Limerick Forest, and along fencerows and various other woods. We’ve measured a trunk diameter of 18 cm along the Jock River south of Richmond, and Wikipedia gives a maximum height of 7 metres.

Native species displaced: All understorey shrubs and herbs, forest tree regeneration.

Uses: None known to me, but Wikipedia says the bark, if dried for a year, can be used as a laxative, that the charcoal is prized for gunpowder, the wood was formerly used for shoe lasts, the bark yields a yellow dye, and that the unripe berries furnish a green dye.

Prevention: Recreational slashing, and the same removal methods listed for the other species; some dense stands in Limerick Forest have been sprayed with herbicide to clear the forest floor. There’s also a native species of Buckthorn, Rhamnus alnifolia, a species-at-risk which is found in bogs and other wetlands. I’ve been saying for some decades that somebody should identify all of the insect pests that keep the native Buckthorn rare, get them into a greenhouse, and select strains of the pests that will go after one or the other of the European species, but nobody has done this yet.